One of the many powerful features built into ProjectControls.online is our automated schedule analysis tools, including the DCMA 14-Point Assessment. In a previous article, Understanding Schedule Analytics | DCMA 14-Point Assessment, we introduced the industry-standard evaluation of schedule quality and health. In our experience, when we employ the DCMA 14-Point Assessment, we have noticed common and persistent issues with the schedule inputs. In this article, we review some best management practices for activity relationships and the use of lags and leads.

Overview

Of the 14 metrics of schedule health included in the DCMA 14-Point Assessment, six (6) evaluate schedule inputs, including missing logic, relationship types, lags, and leads. DCMA’s emphasis on these project inputs is generally accepted, but not widely understood. Let’s look at why DCMA has chosen these metrics and how they influence schedule integrity.

Missing Logic

The logic check is the easiest metric to understand but unfortunately is not consistently achieved. The Missing Logic metric seeks to ensure that all incomplete activities have relationships to other activities, i.e. predecessors and successors. Just one missing link can have a significant impact on the project completion date or critical path and could be imperative to the network logic. This metric does not evaluate whether the relationships are accurate; just if they exist.

Relationship Types

DCMA requires that at least 90% of all activity relationships should be Finish-to-Start (FS) relationships. Ideally, all tasks in the schedule would be sequenced this way to have the clearest understanding of the critical path. We will now explore why DCMA puts such a high threshold for this metric. First, here are some plain speak definitions and examples of the four types of relationships.

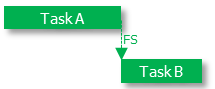

| Finish-to-Start (FS) finishing a task allows the start of another task, anda delay to the finish of a task would delay the start of another task |  |

| Example: the finish of crane mobilization allows the start of pile driving; if the finish of crane mobilization is delayed, the start of pile driving will also be delayed. | |

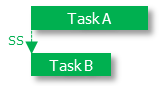

| Start-to-Start (SS) starting a task allows the start of another task, anda delay to the start of a task would delay the start of another task |  |

| Example: the start of vibration monitoring allows the start of pile driving; if the start of vibration monitoring is delayed, the start of pile driving will also be delayed. | |

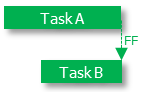

| Finish-to-Finish (FF) finishing a task allows the finish of another task, anda delay to the finish of a task would delay the finish of another task |  |

| Example: finishing pile driving allows the completion of vibration monitoring; if pile driving is delayed the finish of vibration monitoring will also be delayed | |

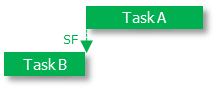

| Start-to-Finish (SF) starting a task allows the finish of another task, and a delay to the start of a task would delay the finish of another task |  |

| Example: the start of permanent power allows the completion of temporary power; if the start of permanent power is delayed, the finish of temporary power will also be delayed * NOTE: these relationships are very uncommon and should be rarely used in schedules. | |

So, if there are obvious reasons to use smart relationships (SS, FF, and SF) to accurately model activity dependencies, why does DCMA discourage or restrict their use? Pervasive misuse that undermines the Critical Path Method.

Smart relationships may be used in cases where it is the true nature of the dependency. However, SS and FF relationships are more often used to avoid adding schedule detail and to schedule activities in parallel that do not truly depend on each other. Moreover, SS and FF relationships, in combination with lags (discussed next), are used to model hidden dependencies, such as crew, equipment, or other sequencing constraints. After a quick discussion about lags, we will show how relationship misuse affects the critical path.

Lags

A positive lag between tasks, where a task starts some number of days after the start or finish date of its predecessor, is a frequently misused scheduling relationship that can adversely affect analysis of the project critical path. When drawn in a network diagram, the lag clearly begs the question: what is significant about this particular period between the activities? Often, the reason for the lag could be replaced by an activity that more visibly and clearly models the dependency. A common example: between activities for “Place Concrete” and “Strip Forms”, schedulers will employ a lag that represents concrete cure time; but the time is more appropriately modeled as an activity with FS dependencies to the other activities.

The use of lags is most common with SS and FF relationships, which further complicates CPM calculations. Next, we will look at a common example that demonstrates lag misuse and how it can be avoided.

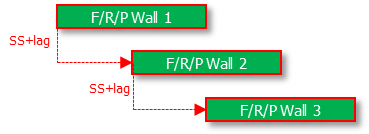

Many construction projects, both vertical and horizontal, encounter repetitive task sequences for building something concrete, relatively quickly. All to often, schedulers combine the activities of building forms, laying rebar, and placing concrete into one activity, by location or project element, eg. F/R/P Wall 1 may appear to represent Form, Rebar, and Pour Wall 1. In most cases, the location is not the driver—the resources are. In our example, the F/R/P Wall 1 activity may involve a carpentry crew to build forms, ironworkers laying rebar, and a labor crew placing concrete. Typically, the start of a second location does not depend on the completion of the first location; it depends on the availability of crews. Many schedulers, having already segregated the work by location, deploy SS or FF relationships with lags to model the flow of crews through the work. We can see how scheduling this way plays out in the example below.

PROBLEM:

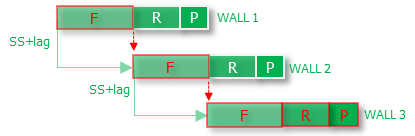

The project team has determined that the formwork crew needs the most time; therefore, Walls 2 and 3 will start when the formwork crew is complete with the previous wall. Having organized the work by location, the flow of the formwork crew is modeled with a lag between wall locations, resulting in all activities being critical. However, breaking the activities down into tasks driven by crews, not location, would reveal a more accurate critical path, as intended.

As Typically Modeled As Intended

The difference is insignificant if everything goes as planned. Yet – experience tells us that projects often do not go completely as planned. If forming Wall 1 takes more time than planned and we scheduled our activities using the “Typically Modeled” then duration as scheduled is not affected and it could be argued no impact occurs. In reality, the finish of wall construction will be delayed had we shown the work “As Intended”. As our example demonstrates, replacing a resource or equipment dependency with a lag can directly impact the calculation of the critical path and obscures the efficient scheduling of multiple crews.

SOLUTION:

The answer is simple: replace lags with activities and finish-to-start relationships. In our example, we would create activities for the known work activities that make up the wall construction based on the resources that drive the schedule.

It should be noted that adding schedule detail to remove all lags may be impossible or not cost effective. DCMA provides some leniency with this metric, setting the threshold at no more than 5% of total task relationships remaining may contain lags.

LEADS

A lead is simply a negative lag, or the amount of time an activity can start before the completion of its predecessor. On the surface, this appears like a useful scheduling tool to add concurrency to sequences, allowing activities to get a head start and run in parallel to other related activities. But, unlike positive lags, DCMA forbids the use of leads because they have adverse effects on the project total float, impeding the ability to determine the true critical path.

Think of it this way: a lead allows the actual start of an activity ahead of the predicted finish of its predecessor. What if the predecessor doesn’t finish on time and the successor has already started? By contrast, using positive lags, at a minimum, allows the actual start or finish of an activity after the actual start or finish of its predecessor.

EXAMPLE PROBLEM

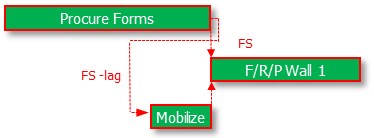

We see Leads often used with FS relationships on longer activities in order to model that a related activity would start near the end of the long duration activity and doesn’t need to start sooner. In our example at right, the start of F/R/P Wall 1 depends on the completion of form procurement and mobilization. Procurement is expected to take much longer than mobilization. As a result, schedulers often add a FS with a negative lag between procurement and mobilization.

Thinking from a CPM mindset, this logic forces mobilization “as late as possible”, which removes its total float and makes it a critical activity. The scheduler is trying to model the desired efficiency of mobilizing “just in time”, avoiding inactive crews while procurement is completed; but, this is exactly what happens if procurement is delayed after mobilization has started.

SOLUTIONS

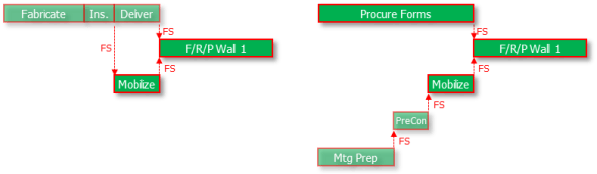

How can we use better logic and model the schedule that we intend? DCMA accepts the use of positive lags and smart relationships; so, one method would be to exchange the FS and negative lag with some combination of SS or FF with (or without) lags. In our example, a FF relationship with no lag between Procure Forms and Mobilize improves the CPM logic and enforces the same timing for mobilization. Conceptually however, the finish of Procure Forms does not allow the finish of mobilization. Using a FF and no lag may be preferred, but the activities’ finishes do not actually depend on each other.

Scheduling best management practices and DCMA promote the use of FS relationships whenever possible. Therefore, a preferred solution would be to decompose the work to a level of detail in which traditional FS relationships can be used, or add activities for work that precedes mobilization, examples of both shown below.

Summary

The DCMA 14 Point Assessment emphasizes metrics on missing logic, relationship types, lags, and leads. This article reviewed why these metrics are so important and provided best management practice guidance. In summary, as much as is reasonable, the activities within the schedule should be decomposed to a level of detail where finish-to-start relationships with no lags comprise most of the schedule. Start-to-start and finish-to-finish relationships should only be used when they represent the true nature of the dependency and can not be decomposed further. Lags are permitted by DCMA but should be minimized as encouragement to more properly organize and link the schedule. Leads are never permitted and must be replaced by better logic and/or activity decomposition.

If you have questions or comments, don’t hesitate to contact us at admin@projectcontrols.online.

Leave a comment